Apache Kafka

April 20, 2025

TL;DR

Kafka is a system for reading from, writing to, and processing series of events across multiple computers so that events are not lost and can be processed reliably at any scale. It works by storing event data across multiple servers called brokers and enabling client services to communicate through the brokers in a fully decoupled manner.

Preamble

If this isn’t the first post you’re reading from my blog, you may have noticed I struggled with understanding Apache Kafka. I know it’s a service that enables distributed event streaming processing, but that explanation doesn’t cut it for me. I don’t get that “feeling” I get when I understand something intuitively.

Therefore, I hope you leave this page with a clearer understanding of what Apache Kafka is, what it does, and why it matters. Here’s my take – hope you enjoy it.

Contents

- Intro

- The Issue With the Traditional Approach

- Shift Towards Event-Driven Thinking

- So What’s Kafka?

- Let’s Finalize This

Intro

Let’s start with a scenario: your business needs to instantly know and respond to everything happening across your organization – whenever a customer clicks on a product, whenever they cancel their order, whenever they delete an item from their cart – all as it happens. This is what Apache Kafka enables.

In this post, I’ll break down what Apache Kafka actually is in plain english, why it matters, and why the explanations I got from Perplexity left me, well… Even more perplexed.

Even if you are a dev like me who has never worked with event streaming, understanding Kafka will help make sense of why companies like Uber and Amazon can process massive amounts of events without overwhelming their internal systems. I’ll walk through this post with a problem-solution approach, where I will address an issue with a “traditional” approach and how Apache Kafka helps solve that problem.

The Issue With the Traditional Approach

Traditionally, data in software was built around databases, which represents the world as “digital entities” with “current states.” For example, a restaurant’s current rating, a smart thermostat’s current temperature setting that’s oblivious to the temperature war between roommates, and your fitness app’s record of your current running pace without the fact that it’s your first run in a full year.

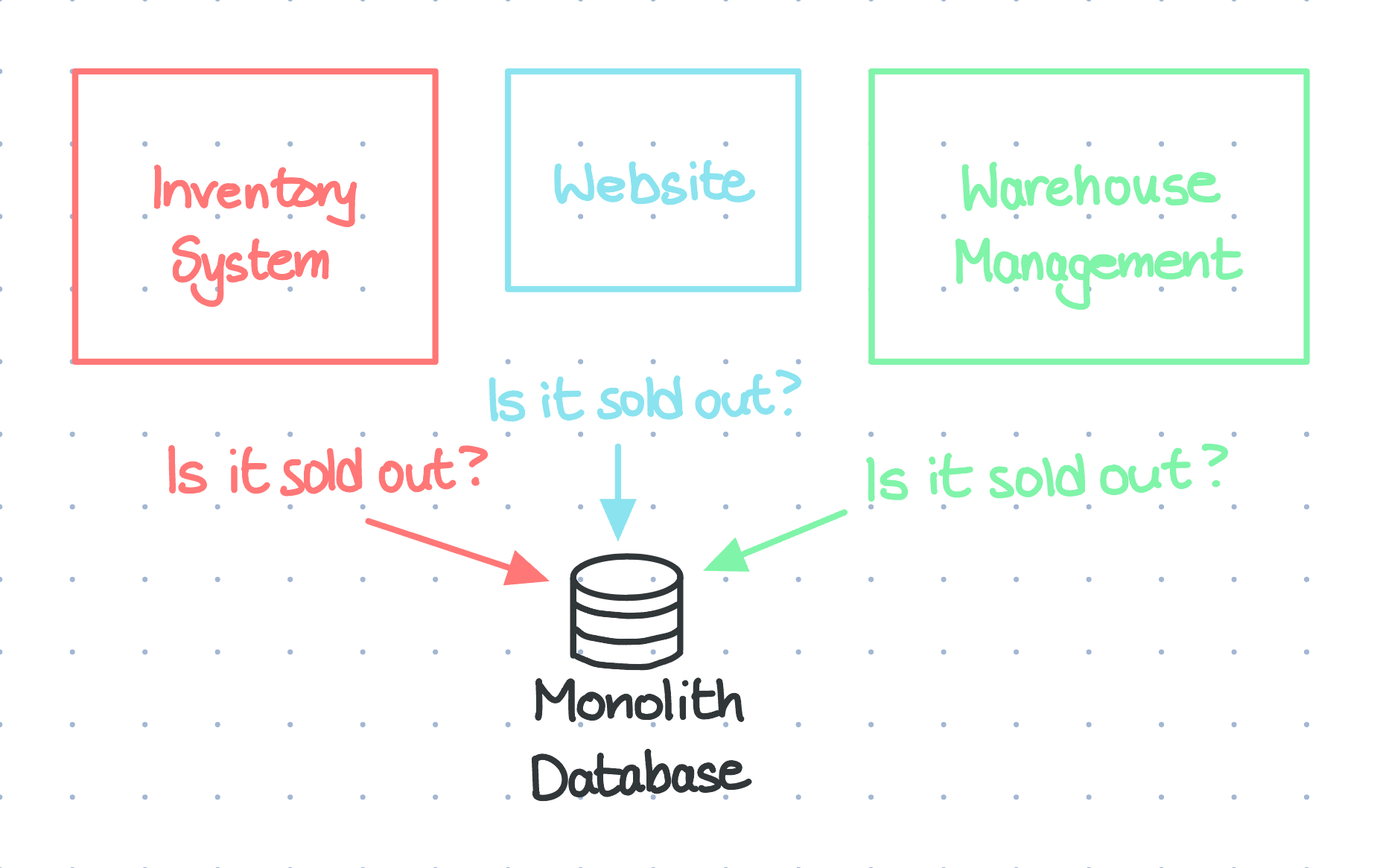

However, as systems grew in complexity, these databases were getting increasingly problematic. For example, imagine an online store with an inventory system service, a website, and a warehouse management service that all need to know when something’s sold out. With a monolith database, all three services are going to be constantly polling the database to see if something is sold out.

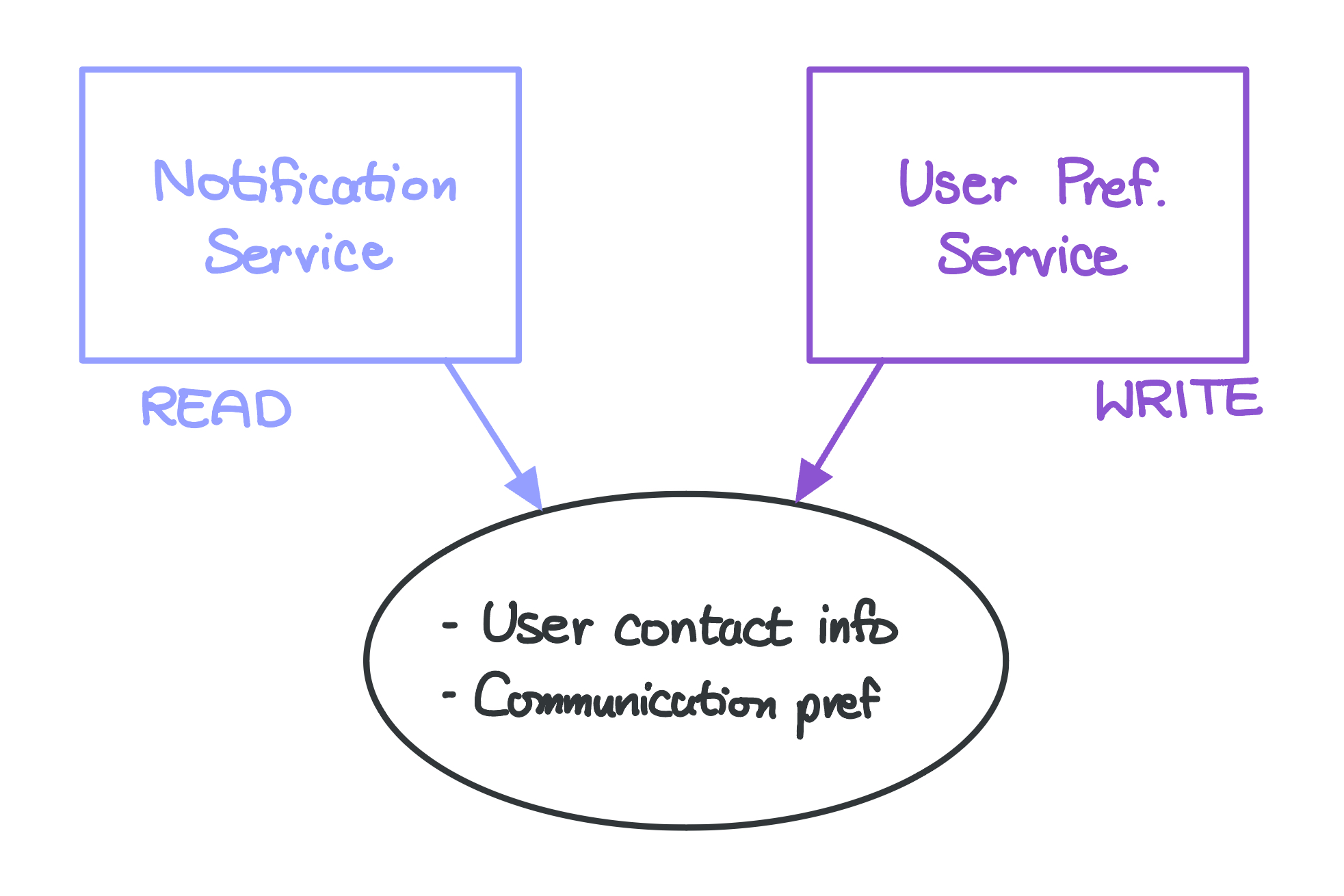

Another example involves an application with a notification service and a user preference setting service. Both services will need access to the users’ contact information and their communication preference settings, but one is going to read from the database while the other writes. Different access patterns – that’s a problem.

Now imagine the application having 10 more of such services accessing the same database, all in different ways, at the same time. Take it even further, what if the database fails?

That’s a nightmare.

Shift Towards Event-Driven Thinking

Here’s where we shift paradigms to using events. Events (also referred to as records or messages) are basically records of something that happened. If traditional databases captured “states,” Kafka captures events, thus why Kafka is explained as taking an ‘event-driven’ approach.

An event might look something like this:

{

"key": "Ael",

"value": "Searched flights to Washington D.C.",

"timestamp": "Apr. 11, 2025 at 20:00"

}

It captures an action that took place – me searching for flights to Washington D. C.

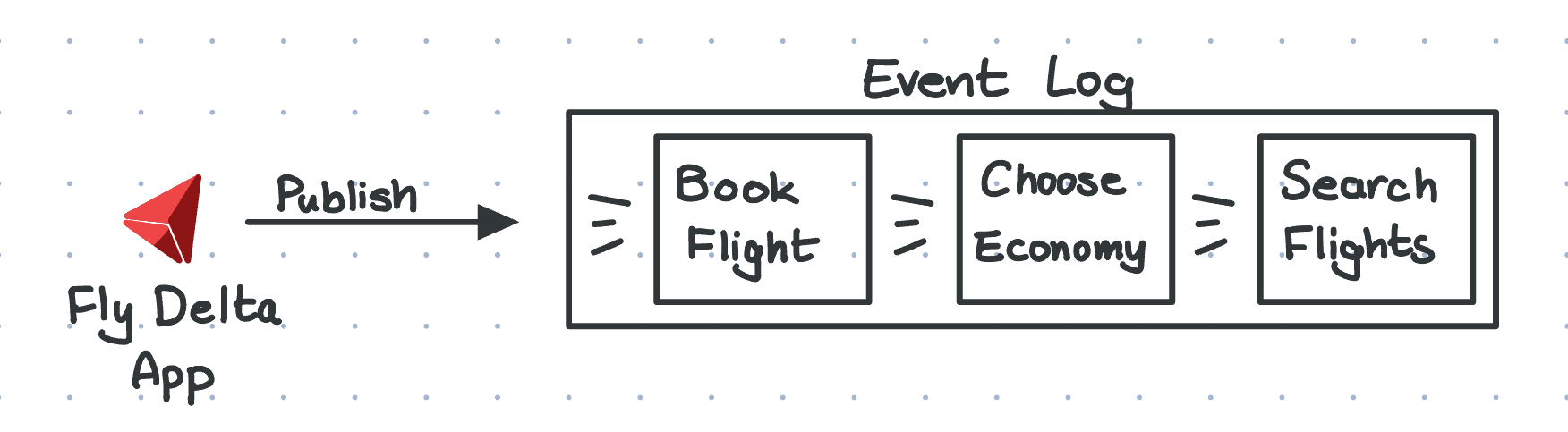

Now an event log is where events are stored, so it might look something like this:

[

{

"key": "Ael",

"value": "Searched flights to Washington D.C.",

"timestamp": "Apr. 11, 2025 at 20:00"

},

{

"key": "Ael",

"value": "Chose basic economy for flight to Washington D.C.",

"timestamp": "Apr. 11, 2025 at 20:05"

},

{

"key": "Ael",

"value": "Booked flight to Washington D.C.",

"timestamp": "Apr. 11, 2025 at 20:20"

},

]

Instead of knowing the final “Ael booked a flight to Washington D. C.,” the event log keeps track of every action I took to book my flight, from searching, choosing to fly economy class (because otherwise it’s 2x expensive), and paying for my flight (after hesitating for 15 minutes).

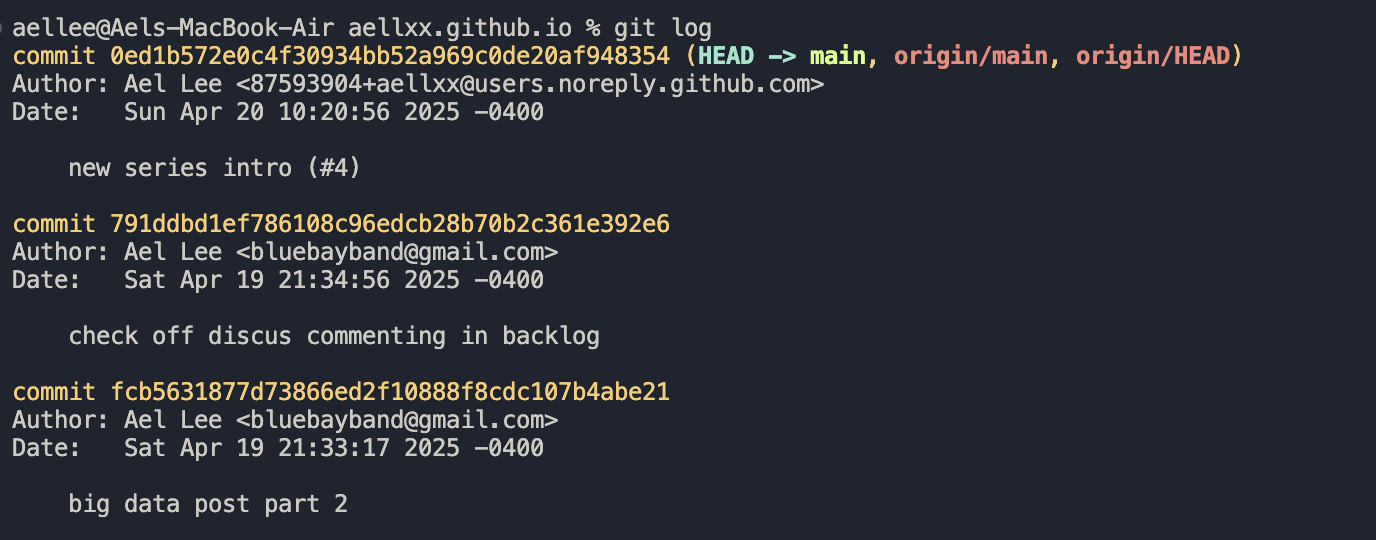

If you’re a dev like me, here’s a realistic example that you’ll probably understand instantly.

Looks familiar, doesn’t it?

When you git log, you can see your commit history. Git doesn’t just store the latest commit, it stores the entire history of how your codebase evolved.

Event Streaming?

Now with a solid understanding of events, what’s event streaming?

Event streaming is the practice of capturing events as they happen (i.e. real time) from event sources, such as databases, thermostats, or software applications in the form of event streams – a continuous flow of events.

Keep this in mind, because it’ll come up in the next section.

So What’s Kafka?

So at this point you might be thinking

You’re taking too long – just give us the explanation 😑

Well I’ll make all the background yapping worth it.

Let’s revisit the Perplexity definition

Apache Kafka is an open-source, distributed event streaming platform designed for high-throughput, low-latency handling of real-time data feeds.

A Distributed Event Streaming Platform

So when you hear that “Kafka is an event streaming platform,” it means it can handle a continuous flow of events.

Now you might ask,

What do you mean Kafka “handles” events?

Kafka has three primary features for handling continuous flows of data:

- It enables services to write to (publish) and read from (subscribe to) event streams

- Events are stored durably and reliably (across multiple computers)

- Services can process events as they occur, or after they happen

When an event streaming platform is distributed, it means that the system runs across multiple computers (servers) rather than just a single server. With your streams spread across multiple machines, a single server failure doesn’t equate to your data being gone – which is what we call fault tolerance.

In addition to fault tolerance, a distributed architecture offers some more benefits:

- Scalability: You can increase throughput by adding more servers

- High Throughput: Multiple servers can process more events simultaneously, versus when you only have a single server

So far, in summary, Kafka is a system for reading from, writing to, and processing series of events across multiple computers so that events are not lost and can be processed reliably at any scale.

How does it work?

Now we have a basic idea of what Kafka is, let’s dive into how it works.

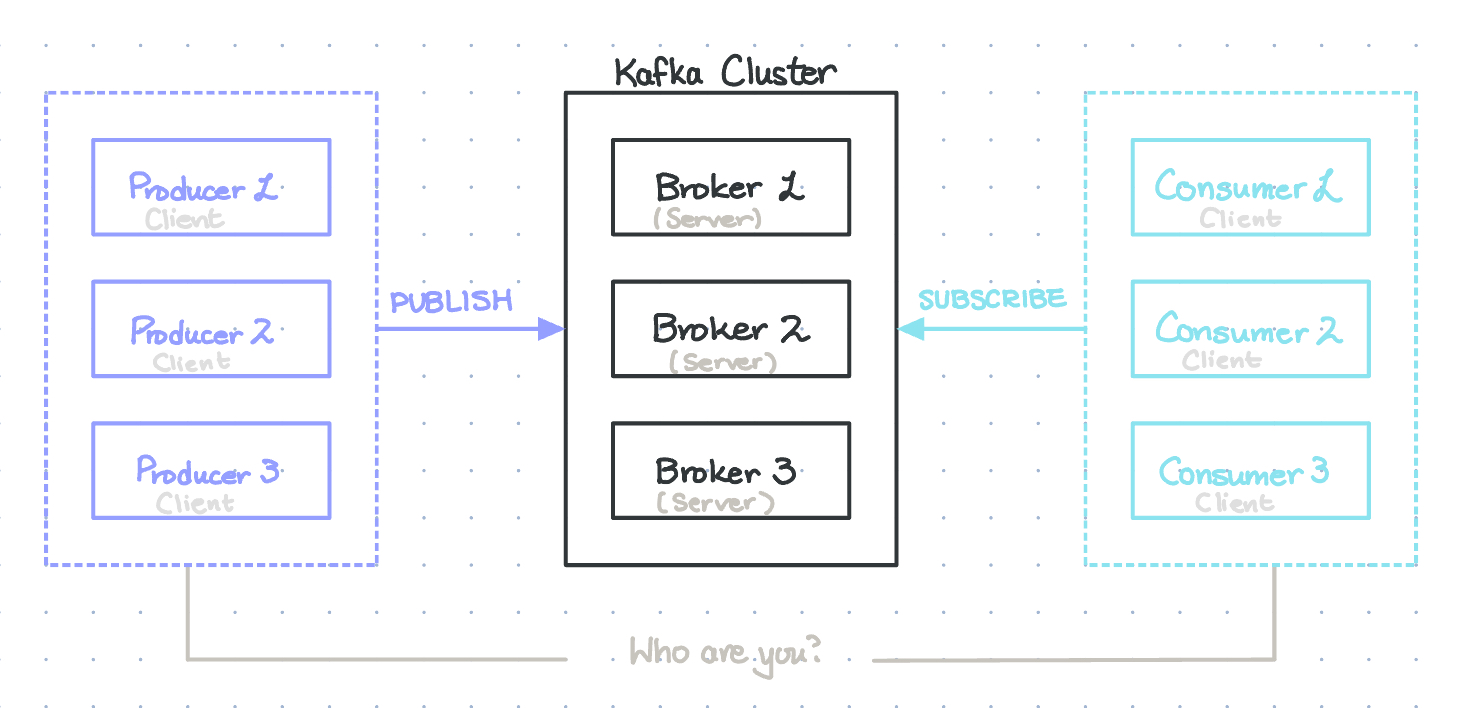

Kafka is a system made up of servers and clients that communicate via the topics. Let’s go over each of the bolded terms.

Servers

Kafka servers run as a group called clusters, and servers in a cluster can be distributed across data centers or cloud regions. These servers fall into two main categories:

- Brokers: These are the actual computers that store the event data and make them available to clients (more on this soon).

- Kafka Connect servers: These servers run Kafka Connect, which helps you to import and export data from existing services like an old legacy database or other SaaS products.

Clients

Kafka clients can be thought of as your applications and/or microservices that read from (subscribe to), write to (publish), and process event streams organized into topics. These clients are designed to work in parallel (thanks to Kafka’s distributed nature) and maintain fault tolerance. Clients also fall under two categories:

- Producers publish, or write, events to Kafka

- Consumers subscribe to, or read and process events.

In Kafka, producers and consumers are fully decoupled, meaning they operate independently of each other. Publishers can publish messages without knowing/caring about which consumers will read them, and consumers can read messages without knowing/caring about who published them.

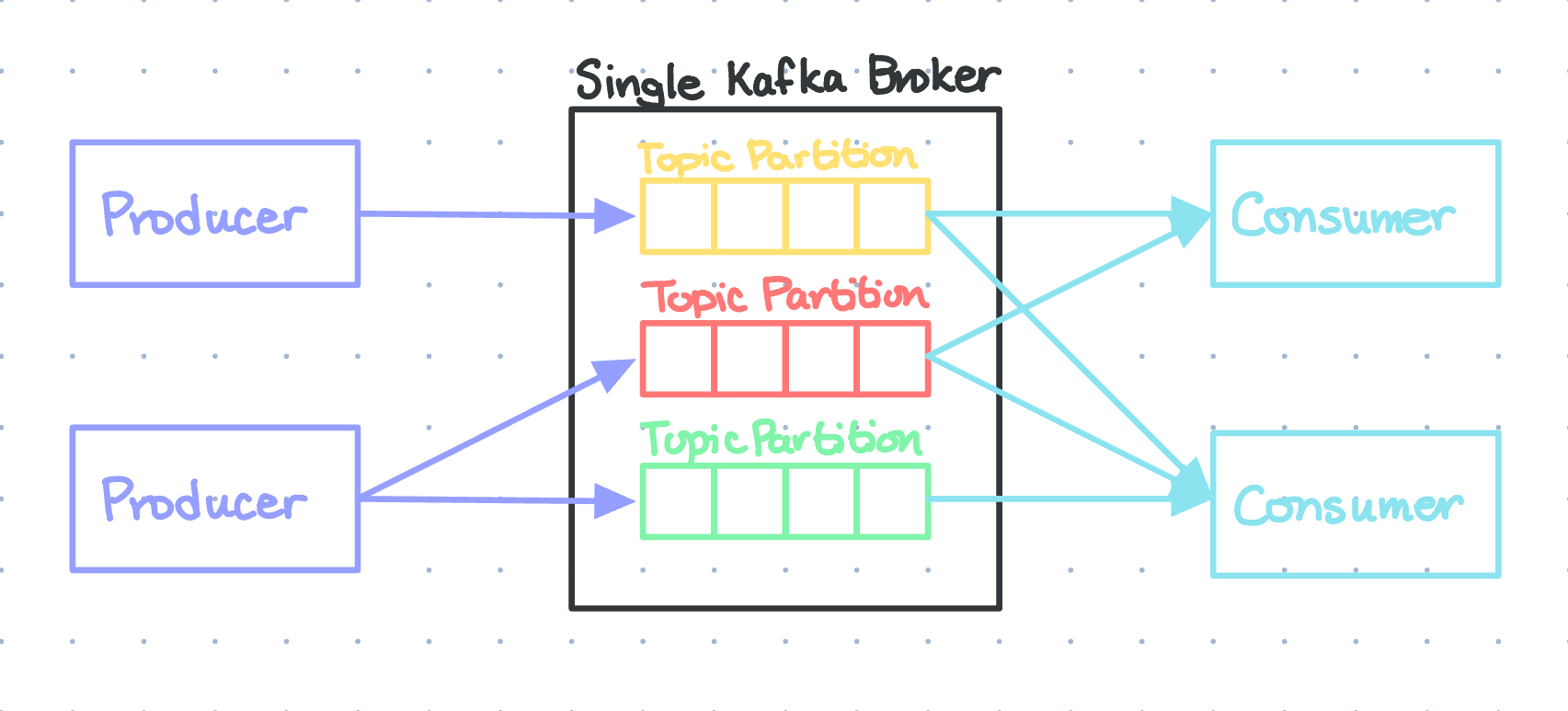

Topics

Topics are basically the Kafka lingo for event logs – where events are stored – and it is how clients and servers communicate. For example, you might have a topic named “flight-bookings” for flight-booking-related events. Topics in Kafka support multiple producers and multiple subscribers - a single topic can have zero, one, or many producers writing events to it, as well as zero, one, or many consumers subscribing to these events.

Topics are partitioned, meaning they’re spread across multiple “buckets” on different Kafka brokers. This distribution is crucial for scalability as it allows client applications to simultaneously read and write data from/to many brokers. When a new event is published, it’s appended to one of the topic’s partitions. Events with the same key (like some kind of ID) are written to the same partition, and Kafka guarantees that consumers will always read a partition’s events in exactly the same order they were written.

Let’s Finalize This

Ok so here’s the take:

In summary, Kafka is a system for reading from, writing to, and processing series of events across multiple computers so that events are not lost and can be processed reliably at any scale. It works by storing event data across multiple servers called brokers and enabling client services to communicate through the brokers in a fully decoupled manner.

Closing

I’ll admit – that was a mouthful.

But I’ll also admit, I think this helped me understand and internalize Apache Kafka, so I no longer have to cold-memorize the definition when I’m studying for AWS certs.

I’m not very good at closings, but as always, thanks for reading till the end! If you have any questions/comments/feedback/critiques, please do not hesitate to let me know in the comments below.

Until next time,

Ael

Sources

- Intro from the official Apache Kafka Website

- What Is Apache Kafka? (YT Video)