Containerization Pt. 1

May 04, 2025

TL;DR

A container is something you use to package and ship software applications along with all the application dependencies, libraries, and runtime necessary for the application to run.

Contents

Preface

I was a junior in college when I first heard about Docker.

I was a senior working on my senior project when I first had to deal with Docker.

I was 4 months into my professional career when I first had to deploy a containerized application using Docker.

I am 10 months into my professional career, and I have to VERY lightly deal with Kubernetes.

So, if someone asks me, “What is a container? What is Docker? What is Kubernetes?” can I answer it?

Yes, but no.

I can say, “Oh, it packages up your code and dependencies and basically solves the ‘it works on my machine’ problem.” But do I truly understand it? Not really. That’s why I’m here, writing this post — to break it down and finally grasp what containerization is all about.

If this is your first time in this series, welcome to I-should-know-this-but-I-don’t. It’s where I tear apart tech concepts on the internet and try to internalize them. If this is your second time – given this is my second post – welcome back, I’m happy to see there are people like me out there.

It’s probably obvious at this point, but in this post, I’ll give my take on containers, Docker, and possibly Kubernetes. This might be split into multiple parts, but with my continued exposure to containerized services, I just need to get it off my chest that I don’t know know containerization.

So, without further ado, let’s start with the very basics: servers.

Servers

servers

You probably have heard this term a million times by now, I know I have. However, this term was still very intangible, and I often used it without fully wrapping my head around it. I realized part of this came from how “server” has different nuances, and I found myself confused whenever it wasn’t super clear on which server people were referring to. I don’t want that to happen in this post, so I wanted to make sure I cleared the grounds before officially going into this post.

The servers that confused me the most were these two: Server software: Programs that receive requests from other programs, called clients, to supply clients with the resources they need. e.g., Nginx is a web server software that runs on a physical or virtual machine. It is the program that receives, processes, and responds to requests from clients like web browsers. Server hardware: Physical machines with components like a CPU, RAM, and storage, to run operating systems and applications.

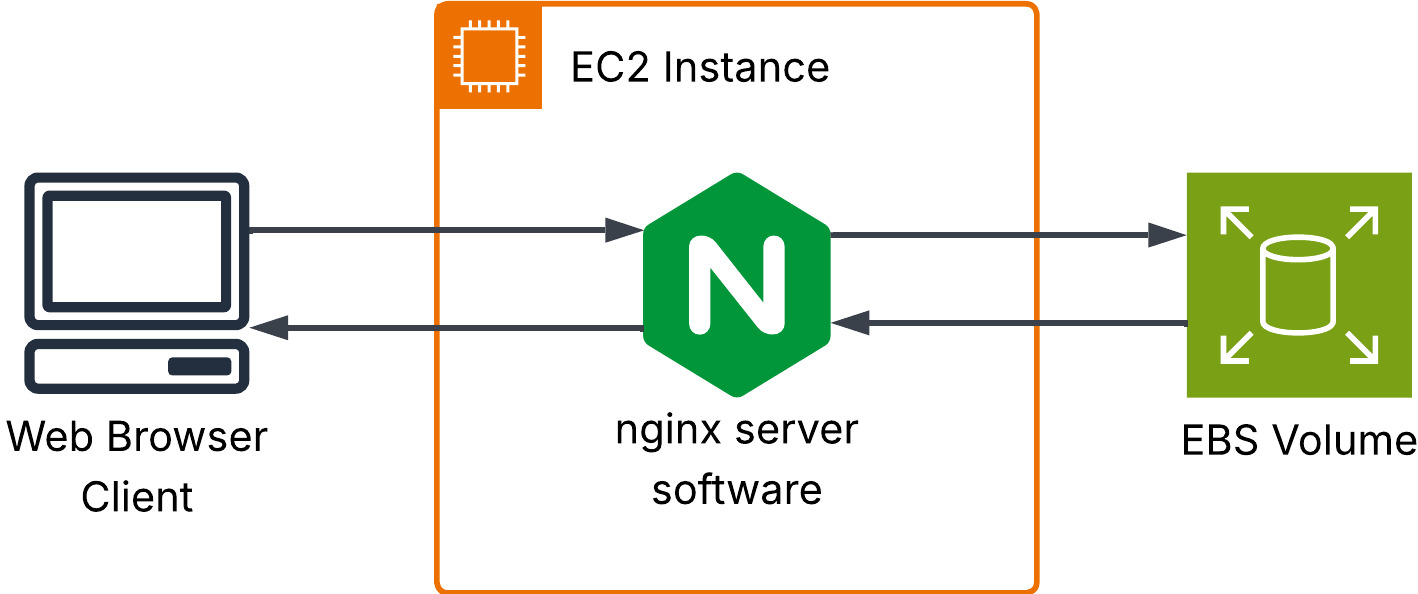

Now, the diagram below isn’t an example of a server in a hardware sense, but this is what it means when you hear “install nginx on your EC2 instance.” EC2 instances are virtual servers you can run on AWS, and don’t worry, there’s going to be a whole section dedicated to virtualization in this post. For now, just know that the word “server” is used interchangeably between server software and the actual physical/virtual machines that enable the server software to run.

Even at the risk of this post getting too wordy, you can expect me to make the distinction clear Every. Single. Time.

End of chapter -1.

Physical Servers vs. Virtual Machines

Physical Servers

Now onto chapter 0.

To understand containers better, we need to understand what issues they resolved, and to understand the issues they resolved, we need to understand the sources of the issues.

Let’s bring physical servers to the table. FYI, I referred to them as server hardware in the previous section. To reiterate, the server hardware has the actual, physical things like the CPU(s), memory, storage (either hard disks or SSDs), and additional GPUs or Add-on cards.

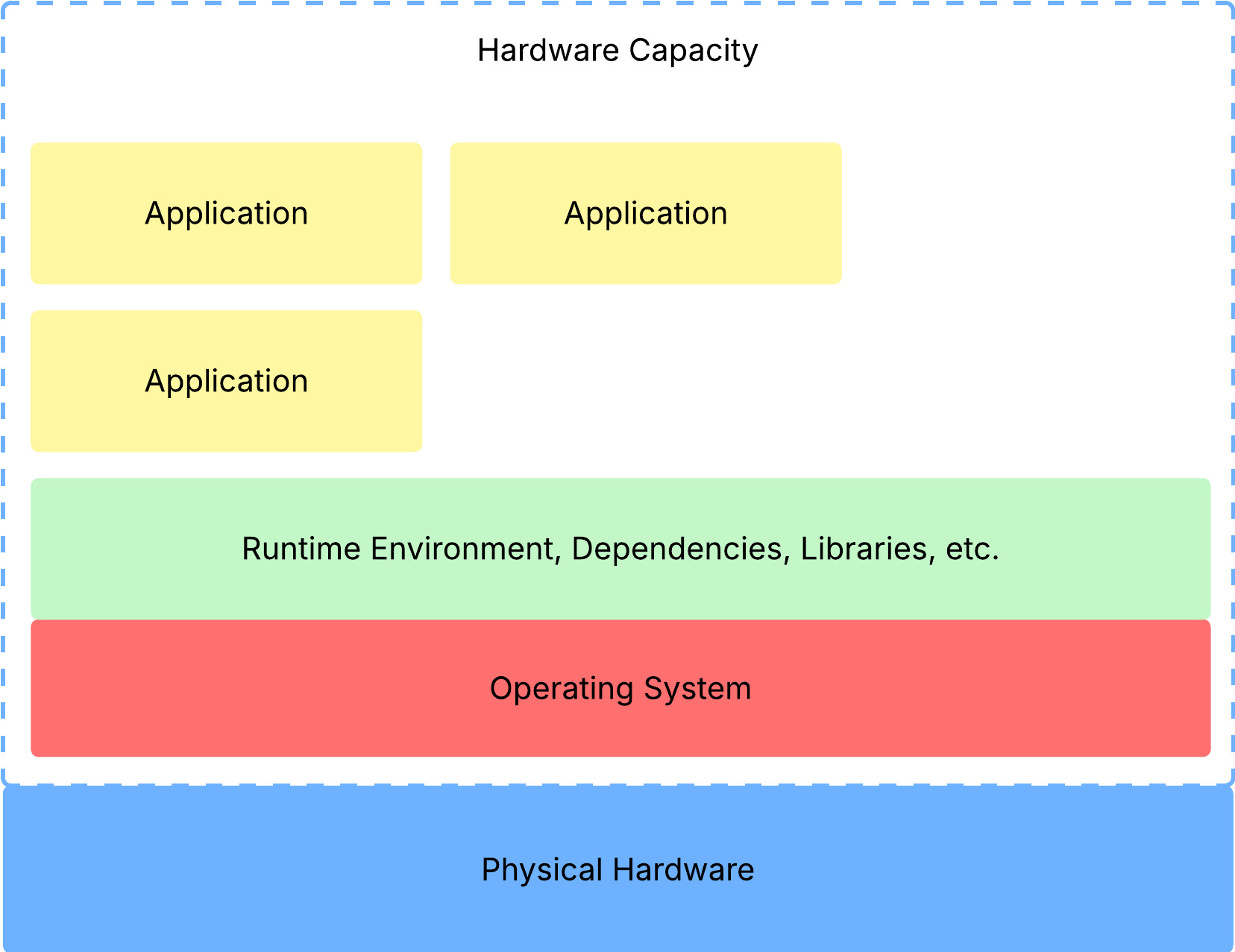

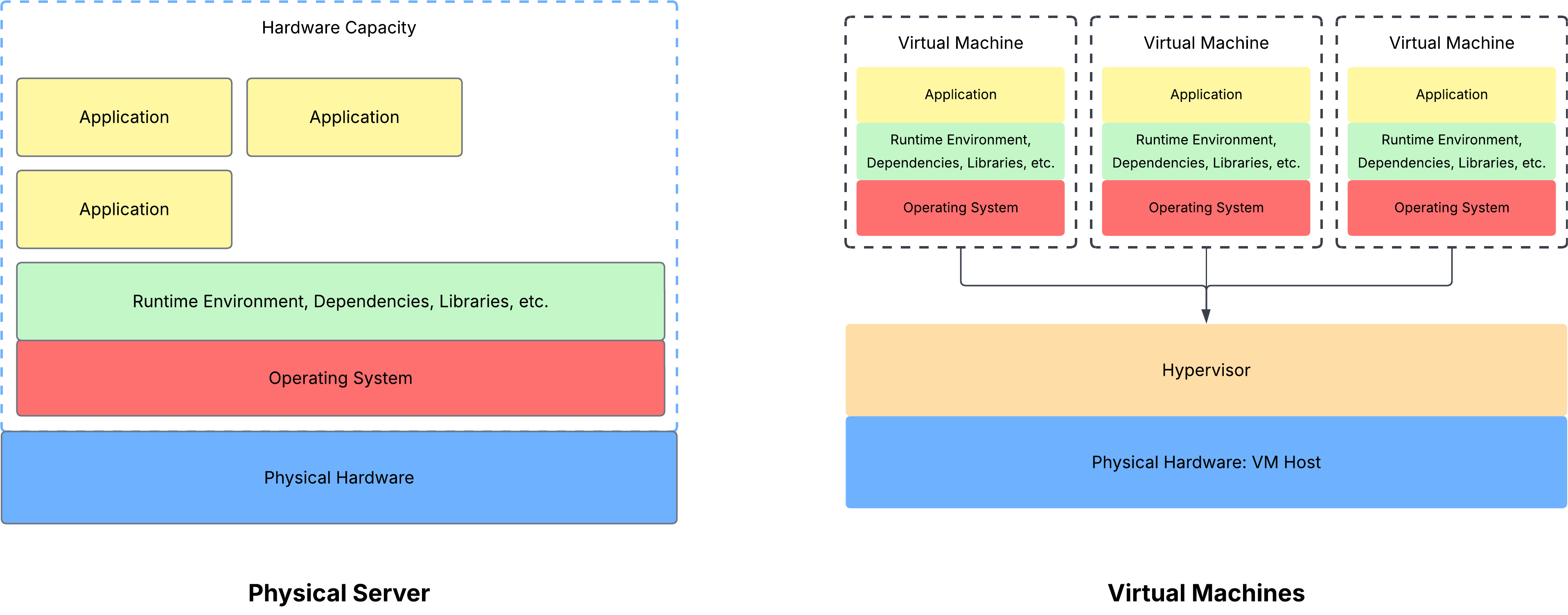

Now, this physical hardware is going to have some capacity. For example, the ability to run a couple of applications, store a couple of files, you name it. Within this capacity, we’ll go ahead and download an operating system, and any runtime environments, dependencies, and libraries. Finally, let’s run some applications that use the hardware capacity.

Now let’s say we’re running a web server software program and a PostgreSQL database in the same hardware capacity (i.e., the software program and the database share the same physical hardware resources).

Your website is live and being used. Your database also stores some random information you scraped from the Internet. All is well.

Until someone comes along and starts throwing a bunch of queries into your database. They are running crazy expensive JOIN operations and CREATE-ing a bunch of tables, populating them with more data than you ever imagined.

Suddenly, you can’t access your website anymore. It’s super slow when loading, and you’re getting complaints from your users that they can’t load your website. This is because one application is hoarding all the hardware capacity, leaving none for your other application.

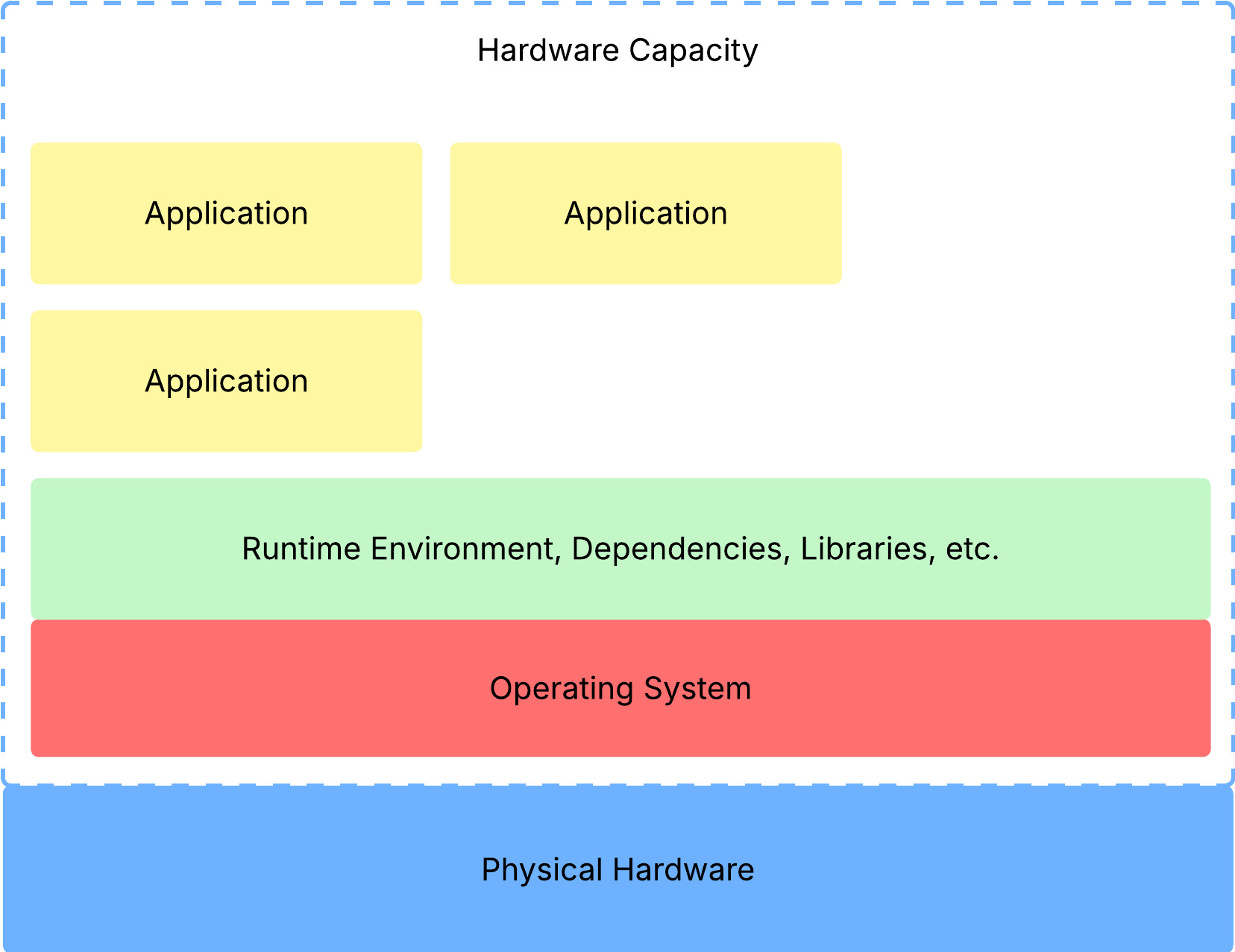

Another major problem is resource underutilization, which is shown in the image above – all those blank spaces left in the “Hardware Capacity” rectangle. Here’s the image once again, for convenience:

Imagine an online clothing retailer that has its own little room with physical devices that host their e-commerce website. This company has invested hundreds of thousands of dollars into their physical server devices that can handle resource spikes up to 85-95% during flash sales that occur four to six times a year, Black Friday, and Cyber Monday.

The problem here is that for the rest of the year, resource utilization remains in the 5 - 25% range, depending on the time of day. So, if we take out a week of high utilization, the company will have a bunch of compute capacity it is not using. To put it shortly: wasting money.

So what’s the verdict?

- Cascading application failures

- Wasted capacity, wasted money

Virtual Machines (VMs)

Before I dive into explaining VMs, I noticed that “virtual servers” and “virtual machines” are used interchangeably, and personally, when I try to learn things, I find interchangeable terms confusing me even more, so let me clarify the difference first.

- A virtual machine is a software-defined system that replicates the functions of a physical machine that has CPUs, RAM, storage, etc. It is virtual because the operating system inside the VM doesn’t get direct access to the actual physical hardware.

- A virtual server is a VM specifically configured for hosting software server programs, like websites, databases, or applications. This term emphasizes the server function of the VM.

In other words, all virtual servers are virtual machines, but not all virtual machines are virtual servers. To keep things general here, I’ll use the term VM. Just note that, with this generalization, the software program running on the VMs can either be server programs (i.e., software that handles client requests like nginx) or just regular programs like Microsoft Excel or Adobe Photoshop.

In the physical server world, there is only a single operating system that sits between the physical hardware and the software programs (libraries, runtime environments, dependencies, and the application). However, in the virtual world, the OS in the VM does not have direct access to the physical hardware. So I guess the next reasonable question is: then what “connects” VMs to the physical hardware?

Introducing the hypervisor.

A hypervisor probably deserves its own post someday, but for the purpose of this post, all we need to know is that

- It is a program that dynamically allocates them to each VM as needed.

- It is a representation of the underlying hardware resources for each VM, making each VM delusional into thinking it has its own dedicated hardware.

Want something shorter? It’s a program that makes virtualization possible.

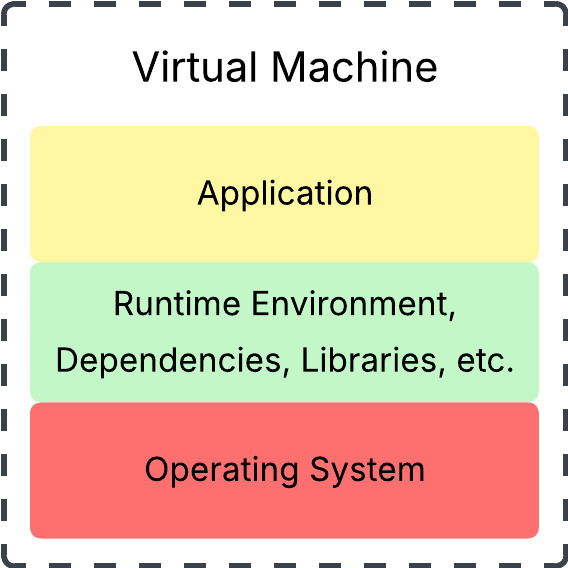

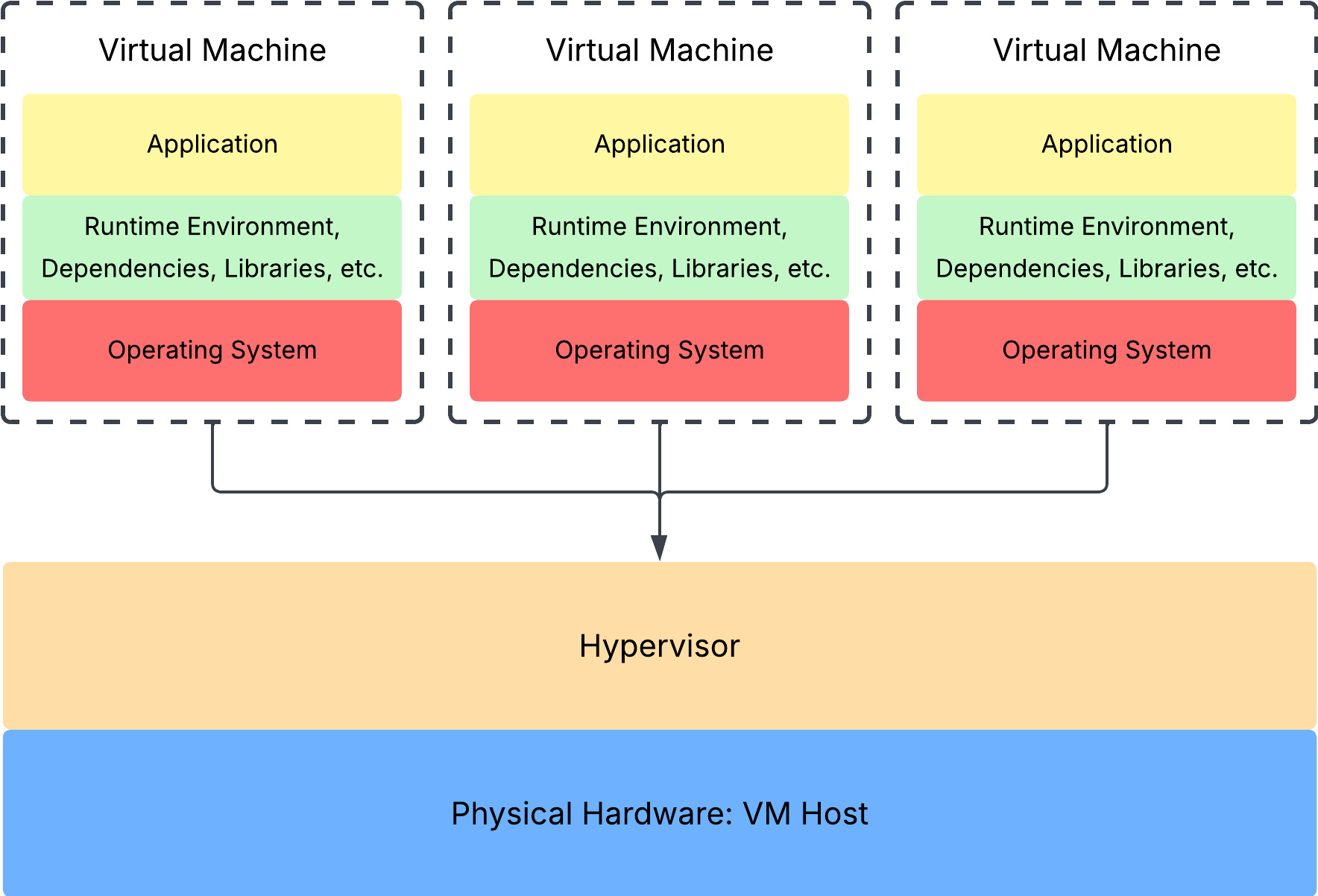

In the virtualization context, the physical hardware resources are referred to as the VM Host. On top of the VM Host sits the hypervisor, which creates hardware delusions for all the VMs that run on it. The VMs themselves have their own operating system, runtime environments (+ the rest), and the application (basically the three components that ran in the “hardware capacity” partition of the earlier physical server diagram).

Here’s a side-by-side comparison:

With the VMs isolated from each other, the two physical server verdicts are solved.

Let’s go through them one by one.

Cascading application failures

With physical servers running multiple applications, a single application failure led to all the other ones failing too. This domino effect is due to all the applications using the same underlying resources. When one application fails, it can hoard all the resources for itself and exhaust the hardware capacity, affecting the performance of the other applications.

With VMs, each machine has its own (virtual) hardware provided and managed by the hypervisor. Going back to the example of an application that fails and ends up hoarding the compute capacity, this is no longer a concern because the scope of the failure is limited to the VM only. So, if you have a database server software and a web server software running in their VMs, the database server software failure won’t cause your website to load indefinitely. The hypervisor might log or alert administrators about the virtual resource exhaustion, but again, the failure will not affect the performance of other applications running on separate VMs.

Wasted capacity, wasted money

With virtualization, you can better utilize your hardware capacity. Because the VMs are completely isolated from each other, there is less risk associated with running multiple applications that use the same hardware. Going back to the e-commerce company example, they can reduce the number of physical server hardware and instead run multiple VMs to host their website. During the times of the year when their network access spikes, they can simply spin up more VMs instead of starting off with a bunch of physical resources that stay idle for 51 weeks of the year. During periods of low utilization, they can use the excess capacity to spin up analytics services and database services to grow their business even further.

+ Others

There are a few other benefits of VMs, one of which is scalability. VMs are easier to get running software because it does not have a hardware component; in other words, they are just software. Therefore, if one of your VMs running a website is getting a surge of traffic, you can simply spin up an identical VM without having to provision the hardware resources that enable the website to run.

In addition, the fast startup helps in scenarios when a VM fails. As I said, the failure will not affect other VMs, but the quick boot and restoration process will also minimize the downtime and enable critical applications to resume much faster than having to replace and set up physical servers.

…But wait

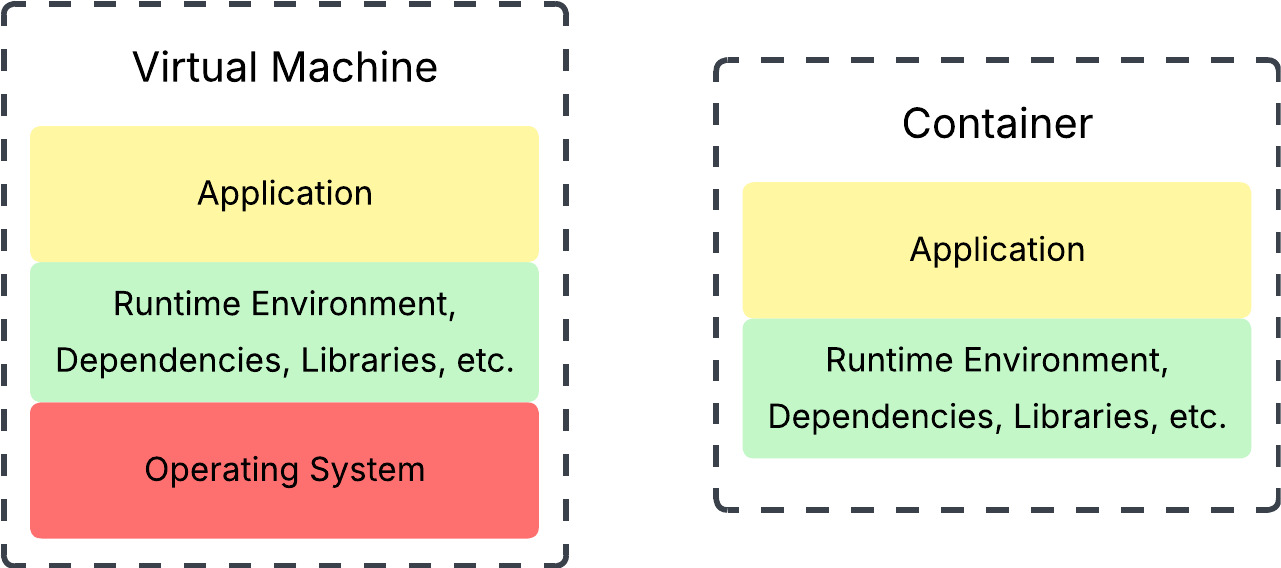

Each VM runs its own OS. Now, what if we have 20 VMs running the same Ubuntu 24.04.2 LTS?

This is the problem with using VMs. If you have something like the scenario I just described, you can end up with multiple copies of the same OS that each consume resources, which – you guessed it – takes up unnecessary capacity.

If you’ve worked in tech, you know we don’t like duplication and having multiple copies of the same things.

So, how do we fix this?

Containers

TL;DR

A container is something you use to package and ship software applications along with all the application dependencies, libraries, and runtime necessary for the application to run.

Ok, now we can start chapter 1.

Let’s start with how the Docker website defines containers (I’ll get to Docker real soon, just know it’s a credible source).

A container is a standard unit of software that packages up code and all its dependencies so the application runs quickly and reliably from one computing environment to another.

Yeah, this is the definition I’ve heard for the last 3 years, the one I used when I pretended to know what containers were. Let’s unpack this in English and based on our understanding of VMs from the previous section. If you understood the previous section, containers will stick to you pretty easily.

When you work with VMs, the physical hardware resources, like the CPU, are virtualized. Each VM runs its own OS, and these individual operating systems do not interact with the physical hardware directly, but through a hypervisor.

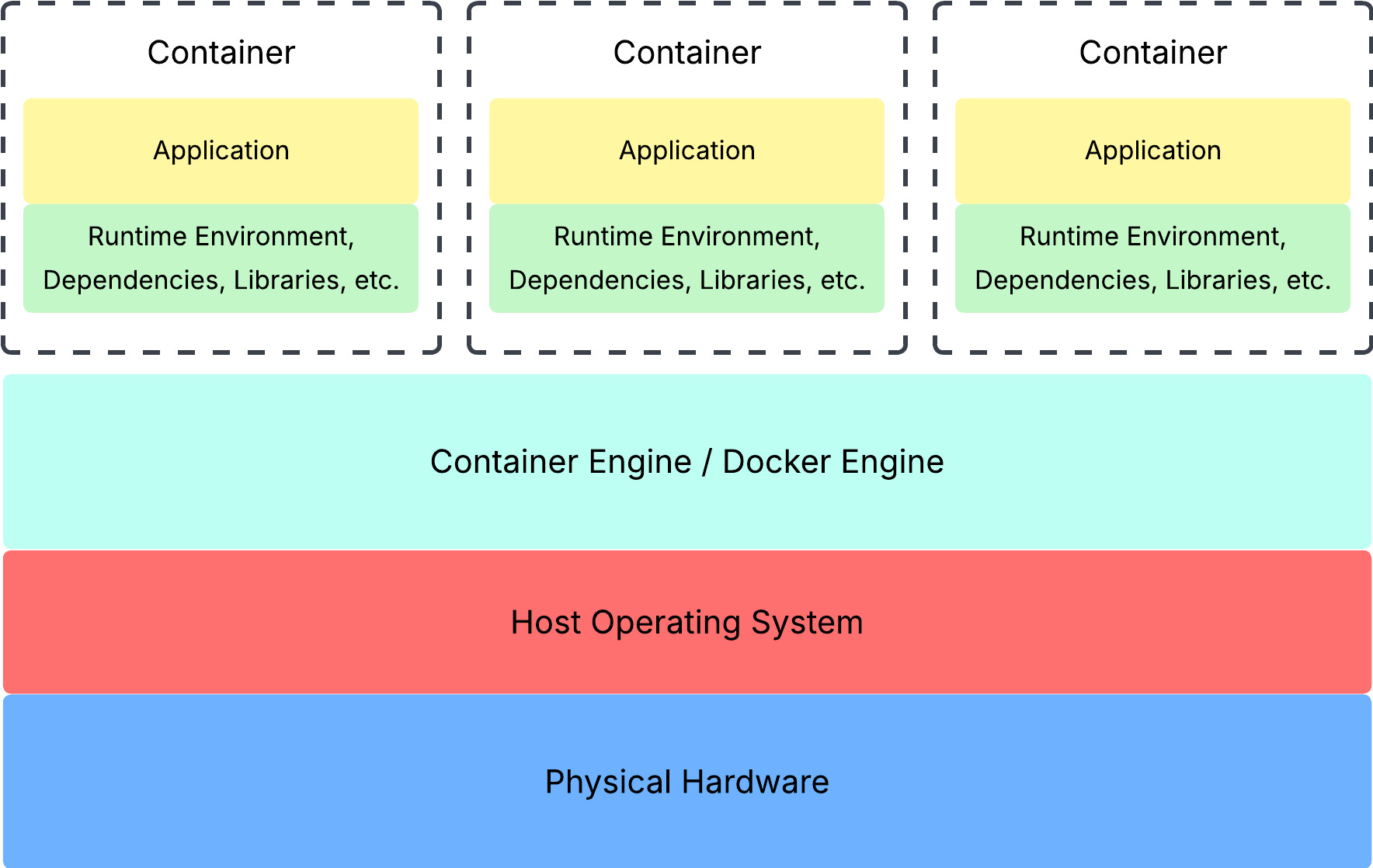

Containers take this even further by virtualizing the operating system itself. While VMs use a hypervisor to simulate the hardware, containers use something called a container engine. A container engine is basically a software that acts as a bridge between your containers and the host operating system. Of course, there is more to this, but I’ll save that for the next post.

With the containers sharing the same host operating system, you can free up even more computing capacity because you don’t need an OS for every container. That is, containers share the same host OS, as if each container is just another process.

Ok, I get what containers do, but what is it?

I’ll take a step back here and give you the dictionary definition of a container:

This definition is from the Oxford Languages dictionary that you can access when you type in “define <word>” in Google. As shown above, a container is something you use to hold or transport something. That something in our case would be the application and the libraries, runtime, and dependencies required to run the application. For example, let me take us back to my senior project I worked on for my senior year: a web application written in Angular.

The container would contain the following:

- The actual code (TypeScript, CSS, and HTML files)

- The Node.js runtime environment (I think we used whatever the LTS version was back then)

- npm packages like the Angular framework and the Supabase library for our persistent storage

Now, if I wanted to run my application on my friends’ computers (not that they didn’t have their own local versions), I would just need to “ship” the container, without having to worry about downloading the same versions of Node.js, Angular, or Supabase, along with thousands of other dependencies. This transportability is one of the key advantages that make containers so revolutionary in software development.

To be continued…

In this post, I’ve gone through the foundations of container technology, starting from the bottom up. However, as you may have noticed, there are still so many things I need to unpack. In upcoming posts, I’ll dive deeper into how containers actually work, so we can get a solid understanding and avoid scenarios like I had to go through – taking Internet definitions and throwing them out there without knowing what I’m talking about.

So I hope you stay tuned for my next post, where I’ll dive deeper into containerization and how containers work!

Feel free to leave comments, questions, critiques, and feedback anywhere, about anything. And as always, thanks for making it to the end.

Hope this helps,

Ael